During WW2, the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR) was formed to confiscate priceless treasures of historical and monetary value from German-occupied Europe.

During WW2, the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR) was formed to confiscate priceless treasures of historical and monetary value from German-occupied Europe.

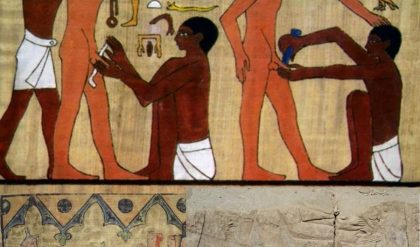

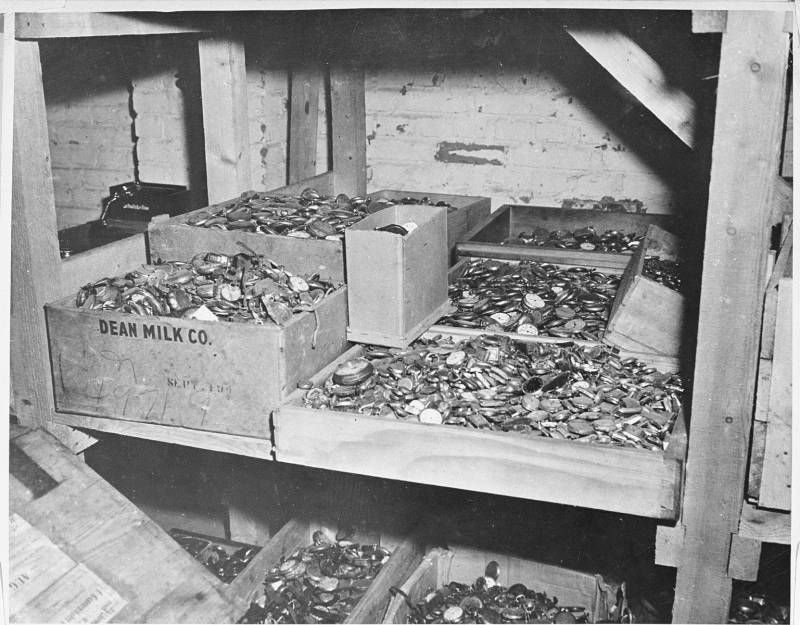

The ERR focused on Jewish and Masonic cultural treasures, encompassing over 21,000 individual objects from Jewish-owned collections, however, this was later extended to anything of value in Jewish homes, businesses and shops, as these objects were now deemed “ownerless” by Nazi decree.

With Nazi expansion across Europe, the collections found in national museums, galleries, churches, and non-Jewish private collections were also looted and carted off to Germany in 1,418,000 railway wagons and 427,000 tonnes by ship.

The most significant objects were designated for Hitler’s unrealised Führermuseum, while some were allocated to other prominent figures such as Hermann Göring.

In the closing chapters of the war in Europe, many of the looted objects were transported by train to underground mines, tunnels, and secluded castles. For instance, Göring’s collection from Carinhall was moved by train southward toward Berchtesgaden in Bavaria.

In 2015, Polish authorities announced the discovery of a Nazi gold train buried at a depth of 8 to 9 metres between Wałbrzych and Wrocław in Poland. At the time, deputy culture minister, Piotr Żuchowski, described how the train was identified using ground penetrating radar.

The discovery was made by Piotr Koper and Andreas Richter, who stated that the train had several train carriages measuring a total of 98 metres, which they believed were transporting weapons and ammunition’s for the Nazi war machine.

However, the pair also cited local legends of a lost Nazi train containing priceless artwork, jewels and gold, likely inspired by the network of tunnels around the nearby Książ Castle, which was part of the vast underground Project Riese complex.

Polish authorities cordoned off the area and deployed police and additional guards to prevent access to the army of treasure hunters who had arrived armed with detection equipment.

Despite an independent study by Kraków’s AGH University of Science and Technology finding no evidence of the train (further supported by mining specialists from the Kraków Mining Academy), excavations of the site continued into 2016.

By august of the same year, the search was abandoned, and Piotr Koper and Andreas Richter were forced to admit that they had discovered “no train, no tunnel”.

They explained to journalists that the train image they interpreted from the ground penetrating radar was in fact a natural rock formation created by underground ice.

The whole debacle led to an increase in tourism for the region, with the major of Walbrzych admitting that “the publicity the town has gotten in the global media is worth roughly around $200 million. Our annual budget for promotion is $380,000, so think about that. Whether the explorers find anything or not, the gold train has already arrived.”

Koper would go on to discover 24 priceless 16th century renaissance portraits that were hidden behind a plaster wall during renovation works of a palace in the village of Struga, Poland.